by Matthew A Williams

History of the Spiritual

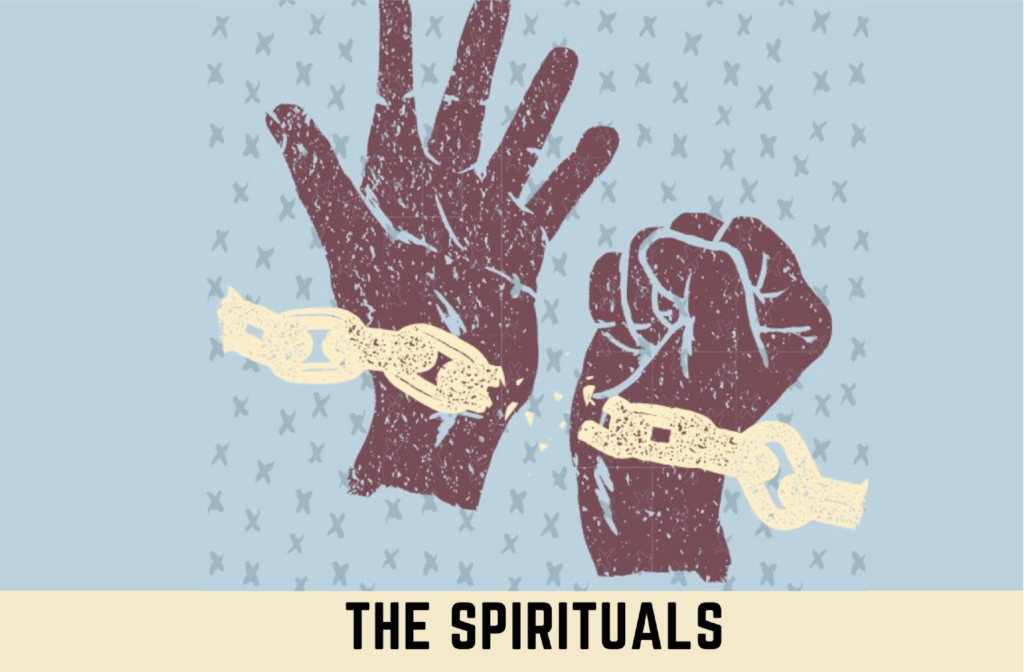

The Spiritual is a style of musical expression created by African captives of the transatlantic slave trade in the American south. Spirituals are a musical record of the individual and shared experiences of enslaved people.[4] Scholars have found evidence of spirituals as early as the mid 1700s, but they came to prominence between 1830 – the 1860s.[2] Historically, there has been some debate as to whether the word ‘spiritual’ should be used to describe these songs. Alternatives have been suggested such as ‘slave songs’, but ‘spiritual’ is commonly accepted.[5]

The term ‘spiritual’ is a reference to one of three types of sacred Judeo-Christian songs categorised for worship at some point between AD 60 – AD 100; they are psalms, hymns and spiritual songs.[2] As the term implies, this music is sacred and expresses the profound realities of the human condition. Though the spirituals can communicate transcendent joy, they also deal with the everyday problems of the ‘here and now’. As the root word ‘spirit’ suggests – this music addresses ideals that are vital to humanity, particularly during periods of intense oppression and suffering.

Folk Spirituals

Folk spirituals are the earliest form of indigenous a capella religious music created by African Americans during slavery.[1] They have their roots in African forms of musical expression. The transportation of enslaved Africans to the Americas provoked significant responses from Africans. There were responses of protest and rebellion but also acts of musical resistance. For example, in 1831 in Southampton County Virginia, Nat Turner (a minister) and his conspirators plotted a slave rebellion that took place on 21st August 1831.

“[during the rebellion] in cultural memory Nat Turner and his conspirators sang the spiritual ‘steal away’. The lyrics read “steal away, steal away home; I ain’t got long to stay here. [6]

It is understood that the lyrics of spirituals often had multiple meanings within the enslaved community and that Steal Away was a veiled message for revolt. Many spirituals carry double meanings, this is one of many features that characterise them.

Many spirituals refer to water, for example, Down to the River to Pray, Wade in the Water or Roll Jordan, Roll. To the slave, water was often a symbol of life, hope and spiritual access to eternal paradise. But it was also used as a coded reference to rivers in Southern slave states that were used as routes to freedom.

Harriet Tubman (1829? – 1913) was known as ‘black Moses’ because, like the biblical character of the same name, she led people out of the bondage of slavery to freedom. Her friends also called her “Old Chariot”.[2] Once Tubman was free of slavery, she took many trips back to the south to liberate others. She was known for using coded spirituals to convey messages to the enslaved. ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’ was used to notify the enslaved of opportunities to escape.[6]

Interpretation

The interpretation of many spirituals was intentionally opaque. Thompson writes that this was about “slaves not wanting whites to understand their private world and also about whites deluding themselves into believing that slaves were docile and happy.”[6] This mask of double meaning was a protective mechanism, it encoded routes toward mental, spiritual and physical freedom from oppression.

As well as double meaning, spirituals have other distinguishing sonic characteristics. Wyatt Tee Walker identifies some key features such as deep biblicism, the use of rhythm (particularly polyrhythm, syncopation), improvisation and ornamentation and antiphonal singing, or call and response.[7]

Spiritual texts have been broadly categorised into two types of textual topic: ‘sorrow songs’ and ‘jubilees’. As the name suggests, the first category identifies those songs that address sorrow, and are usually slow and mournful. Examples would be Nobody Knows the Trouble I See, I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray, Go Down Moses and Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child. The jubilees on the other hand are more celebratory, highly syncopated with a moderate tempo or faster. Examples would be When the Saints Go Marching In and In that Great Getting Up Morning.

Arranged Spirituals

Arranged Spirituals (in contrast to folk spirituals) are “post-Civil war forms of spiritual in a non-improvised form, which evolved in schools created to educate emancipated slaves.”[1] Arranged spirituals were made famous by the Fisk Jubilee Singers beginning in 1871. Formed by George White, the Fisk Jubilee singers began a series of fund-raising tours for Fisk University (a black college). These tours would eventually take the group across the world exposing the western world to the spiritual. Their success also inspired other groups who sang spirituals to do the same.

Performers of arranged spirituals tend to have training in western classical music vocal technique. The vocal quality of the singers who perform arranged spirituals is usually aligned with European ideals of timbre. Arranged spirituals often rely on the printed score and the length is dictated by this. Folk spirituals, on the other hand, could be repeated indefinitely.

Rather than idiomatic folk spiritual heterophony (singing slightly different versions of the same melody at the same time), arranged spirituals have clearly defined harmonic parts. Since the introduction of the arranged spiritual, many singers and composers have brought attention to this body of work particularly within the western European classical tradition. Notable black singers and composers include, Harry T. Burleigh, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, R. Nathaniel Dett, Jessye Norman and many others. Performances are widely available across music platforms.

Spirituals as Inspiration

The spiritual is a style of musical expression that continues to have worldwide appeal. Antonin Dvorak was profoundly inspired by the spirituals.[2] In 1893, he composed Symphony No. 9 in E minor: From the New World, purportedly incorporating the sound of the Negro spiritual. Spirituals such as Swing Low, Sweet Chariot are also regularly sung at sporting events. Countless spirituals reappeared in altered form as freedom songs of the 1960s civil rights movement. In February 2007, the U.S Congress passed a bill naming the spiritual as a “National Treasure”. The spirituals are a critical part of the foundations of American Music. Since the beginning, these songs have resonated with marginalised and oppressed communities; they remain a unifying anthem of hope for all who connect with the profundity of their expressive power.

About the Author

We are delighted to introduce the first post to Biiah’s blog by an invited author, Matthew Williams. His research specialism is in gospel-pop and sacred-secular crossovers and the influence of gospel on pop music. Matthew is a PhD candidate in musicology at the University of Bristol and was the recipient of the University of Bristol 2019 Alumni Bursary. He has lectured at master’s and undergraduate level on topics from African American music to Intertextuality and Semiotics. He has also lectured on the prestigious Fulbright programme on music and The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Matthew currently holds a role as external music tutor at Oxford University. He has a book chapter forthcoming in an edited volume entitled Black British Gospel Music from the Windrush Generation to Black Lives Matter with Routledge Press.

Author Matthew Williams

References

[1] Burnim, Mellonee, and Portia Maultsby. African American Music, An Introduction. Second edition. New York: Routledge, 2015.

[2] Darden, Robert. People Get Ready! A New History of Black Gospel Music. Reprinted by Bloomsbury Academic 2013. New York: Bloomsbury, 2013.

[3] Parrish, Lydia, ed. Slave Songs of the Georgia Sea Islands. First Edition. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1992.

[4] Price III, Emmett George, Tammy Kernodle, and Horace J. Maxile, Jr, eds. Encyclopaedia of African American Music. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2011.

[5] Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. Third Edition. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1997.

[6] Thompson, Katrina Dyonne. Ring Shout, Wheel About: The Racial Politics of Music and Dance in North American Slavery. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

[7] Walker, Wyatt Tee. ‘Somebody’s Calling My Name’: Black Sacred Music and Social Change. Valley Forge, Pa: Judson, 1979.